Kub's Den

Do We Have Enough Storage for 21.9 Billion Bushels of Grain?

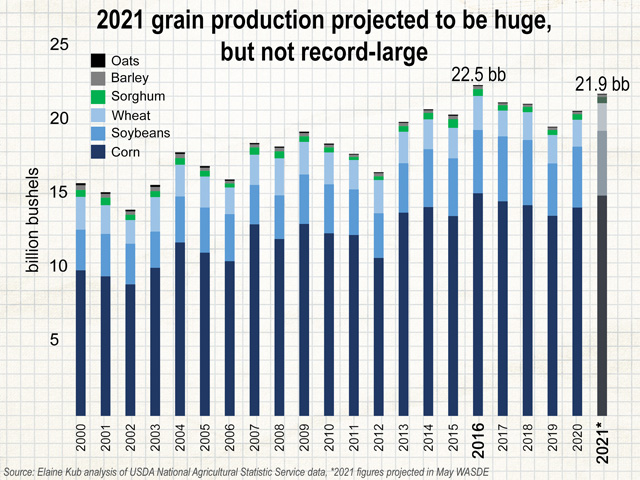

It hasn't happened yet, and there's a lot of dry, hot summer to get through before it does, but the United States is projected to produce almost 22 billion bushels (bb) of commodity "grain" in 2021 (including only corn, soybeans, wheat of all varieties, sorghum, barley and oats).

We will have enough bin space.

For a while there, when some were prognosticating that the nation's farmers would plant more than 92 million acres (ma) or 93 ma of corn (depending how wild their imaginations got), and we would see more than 15 billion bushels (bb) or 16 bb of corn production in 2021, it was almost enough to make a person get bullish about steel prices and bin-building companies. Even now, after the official 2021 corn production projection from the May World Agricultural Supply and Demand Estimates (WASDE) report came in at "only" 14.99 bb, I'm not saying building more grain bins are ever a bad idea. Each on-farm grain bin gives each individual producer more marketing power, and each off-farm grain bin gives each grain-trading firm an opportunity to handle more bushels. But it doesn't look like the total volume of grain that the industry will have to handle in the 2021-22 marketing year will be anything we've never seen before.

P[L1] D[0x0] M[300x250] OOP[F] ADUNIT[] T[]

The record-large all-grain production figure comes from 2016, when the nation grew 15.1 bb of corn, 4.3 bb of soybeans, 2.3 bb of wheat, and a smattering of other stuff, for a total of 22.5 bb. I only speak so dismissively about sorghum, barley, oats, sunflowers, canola, rice, millet, rye, etc. not because they're not important and profitable crops, but because it turns out that when considering the total volume of grain that the industry will have to handle in any given year, corn is virtually the only crop that matters. When each acre planted to corn will need 180 bushels of storage volume to contain its production, versus each acre of soybeans or wheat that will require only 50 bushels of storage volume, then the corn acreage decision is clearly the dominant influence on overall grain-handling volume for any given year.

For comparison, in 2021, the current expectation from USDA's economists is that we will see 14.99 bb of corn production, plus 4.4 bb of soybeans, plus 1.9 bb of wheat. The "small grains" -- sorghum, barley and oats -- have all lost popularity since 2016 (even sorghum's impressively large projected 427 mb of 2021 production is still lower than its 2016 production: 480 mb). All the grain production estimates from the May 2021 WASDE report, with the exception of rice, add up to 21.9 bb.

One final note about all the specialty grains I've been leaving out of this year-by-year comparison: the nation's largest producer of flaxseed, canola, dry edible beans, navy beans, pinto beans, dry edible peas (and the second-largest producer of lentils and sunflowers) is, of course, North Dakota. But in 2021, the entire state of North Dakota is suffering from drought -- even the sugarbeet fields in the Red River Valley of eastern North Dakota. The vast majority of the state is experiencing D3 "extreme" drought -- that's most of the fields that otherwise would be contributing lentils and canola to the 2021 total grain volume.

Looking ahead to this fall's harvest timeframe, the U.S. grain-handling industry's ability to comfortably accept and store all the projected bushels should have some effect on prices. If we were going to grow so much grain, it wouldn't all fit in existing grain bins and structures, that wouldn't necessarily stop the industry from buying the grain anyway and storing it in temporary bunkers and piles. No doubt about it: if indeed we see these projected 21.9 bb of commodity grain production achieved this summer, much of the corn will be stored in outdoor piles anyway. But it likely won't stretch the industry's already demonstrated (2016) ability to find space for grain.

That removes one potential source of bearishness for new-crop grain prices. Without anticipated panic about where it's all going to fit, new-crop buyers should feel confident about letting prices recover from last week's dip.

Elaine Kub is the author of "Mastering the Grain Markets: How Profits Are Really Made" and can be reached at masteringthegrainmarkets@gmail.com or on Twitter @elainekub.

(c) Copyright 2021 DTN, LLC. All rights reserved.