Ag Weather Forum

What Analog Weather Year 2009 May Say About 2023

You likely have read or heard this saying attributed to the great author and storyteller Samuel Clemens (a.k.a. Mark Twain): "History doesn't repeat itself, but it often rhymes." Long-range weather forecasts have a similar component in their development, due to the influence of weather analog years -- years when atmospheric features similar to the current year were in effect at the start. The DTN long-range forecasting team uses analogs as one element of forecast preparation, and the year 2009 has shouldered its way to the head of the pack at this point in the late winter of 2023. "2009 is very prominent. It is a good example of a year where La Nina switched to El Nino," said DTN Weather Risk Communicator Nathan Hamblin.

With that in mind, a look at the year 2009 is in order. It was a year with a prominent new corn-yield record. However, the full weather story of that year tells much more.

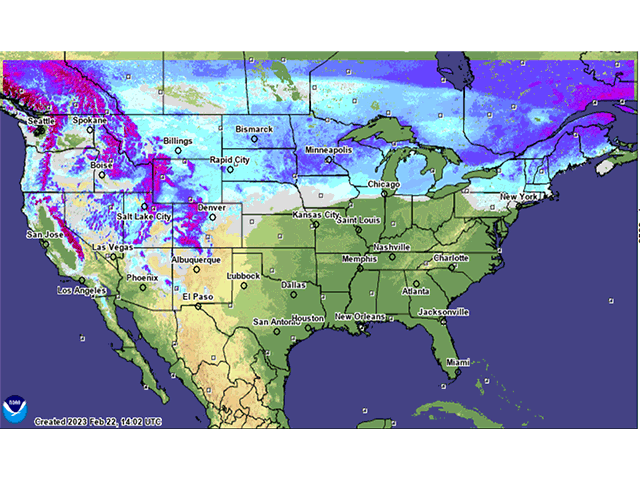

To begin with, there was some thick snow cover. National Weather Service snow cover graphics for the third week in February 2009 indicated snow depth of 10 inches to 27 inches from North Dakota to Michigan. That depth is similar to the widespread near-20-inch deep snow that covers much of the northern U.S. in this third week of February 2023. And, the balance of winter through spring in 2009 stayed cold and wet with numerous planting delays along with flooding, as noted in selected highlights of the USDA 2009 agricultural weather summary:

"In February, precipitation totaled two to four times average in the Northern Plains, setting the stage for another spring of flooding," the report noted. Then, during spring, came flooding and delayed planting, as "... excessive snow and rain brought another spring of flooding to the Midwest and Northern Plains. By March 11, rivers in Missouri, Iowa, Illinois, Indiana, Ohio, and New York had escaped their banks. By late March, the Red River of the North was flooding from near Grand Forks, North Dakota, south to Fargo and beyond ... Flooding continued into April ... With spring precipitation as much as 150% of normal in Illinois and Indiana, wetness in the Midwest caused major crop delays. Spring snows added to the problems for farmers and ranchers," the 2009 USDA agricultural weather summary said.

P[L1] D[0x0] M[300x250] OOP[F] ADUNIT[] T[]

The summer season of 2009 was cool in many northern and central areas as well, especially in July when temperatures averaged from two to six degrees Fahrenheit below normal and the Midwest recorded its coolest July on record. The cool summer led to slow corn pollination progress and subsequent kernel fill. The most notable lag in corn pollination was in the eastern Midwest. Delta and Southeast producers had to cope with a wet pattern as well. In northern areas, small grain harvest progress was as much as three weeks behind average.

Crop season 2009 was not cool everywhere. The Southern Plains had record heat and drought along with severe water restrictions during the spring and summer. Rainfall finally began in late August in Texas.

During the fall, heavy rain in September in the central U.S. hindered the final stage of row-crop maturation and kept soils saturated. October brought more heavy precipitation, which complicated both row-crop harvesting and winter wheat seeding. October also brought a hard freeze to end the season from the U.S.-Canada border to the Texas coast. The impact of the wet fall was prominent. "On Nov. 1, only 25% of the nation's corn crop had been harvested as growers encountered wet fields and higher than normal moisture levels in mature corn. The harvest pace was a month behind the five-year average. Harvest delays of three weeks or more were evident in the six largest corn-producing States ...," USDA's 2009 agricultural weather summary noted. That slow harvest pace meant corn harvest did not truly finish until December, and some acreages in the northern U.S. did not get harvested until the spring of 2010.

DTN Cash Grain Analyst Mary Kennedy was merchandising grain at an ethanol plant in western Wisconsin during 2009. She has memories of "a mess" during harvest.

"I remember the growing season had its ups and downs, and the late freeze that year was welcome," Kennedy wrote in an email. "Then came harvest time and it kept raining on and off and harvest kept getting delayed. Some of the corn we saw had to be rejected for sprout and mold and of course the high percentage of moisture was hard for us to handle. Harvest was pretty much finished in early December when it snowed and at the time of the snow, I remember the entire state left about 23% of the corn standing over the winter."

Corn production and yields, however, both hit new records for the time -- production at 13.2 billion bushels and yield at 165.2 bushels per acre. "Mild temperatures through much of the growing season, combined with adequate soil moisture, provided favorable growing conditions and grain development," noted the USDA 2009 agricultural weather summary.

Those are some of the highlights of the strongest analog year so far in 2023; the year 2009, when production was officially a record, but a year when growers and affiliated ag businesses had to put in plenty of time and labor to make it happen. The question ahead is whether 2023 will rhyme with 2009.

Bryce Anderson can be reached at Bryce.Anderson@dtn.com

Follow him on Twitter @BAndersonDTN

(c) Copyright 2023 DTN, LLC. All rights reserved.