Todd's Take

Keep Raising Interest Rates? The Problems With the Volcker Cure in 2022

In my younger days, I had sports heroes like everyone else, but I have to admit, one of my long-time market heroes has always been former Federal Reserve Chairman Paul Volcker. His ability to squash inflation in the late 1970s and early 1980s was an admirable combination of brains and guts, a courageous move that would have made John Wayne proud.

The main thing Volcker is remembered for is his unwavering determination to let interest rates rise until the inflation fever finally broke. Allowing the federal funds rate to hit a peak of 22.0% in December 1980 was not a popular thing to do and was a lot riskier than handing out WIN (Whip Inflation Now) buttons, but it was the right solution for the right time.

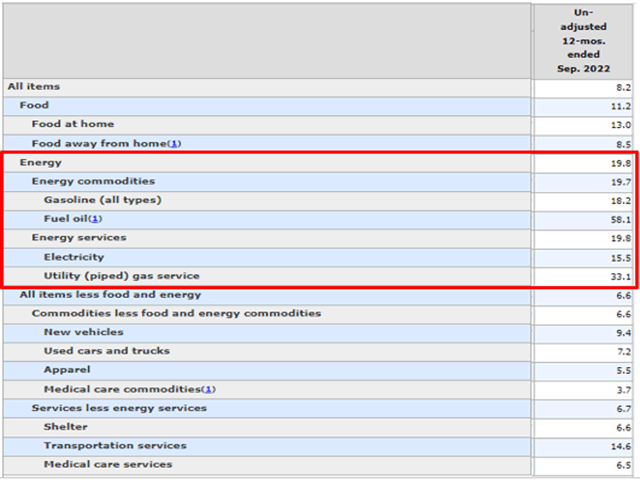

The annual rate of change in the consumer price index peaked at 14.8% in March 1980 and never looked back. Once armed with a stellar example of what to do when inflation comes knocking, Fed officials have kept annual inflation rates below 6.3% for the past four decades.

The inflation of the 1970s that Volcker extinguished was different from today's situation in that it was triggered by President Richard Nixon disconnecting the U.S. dollar from the gold standard in August 1971. The resulting loss of confidence in the dollar sent its value plummeting and, suddenly, Americans found themselves paying more for the purchase of groceries, gasoline and nearly everything else. I still remember parents and grandparents having frequent kitchen-table discussions.

The Arab oil embargo of 1973 did not help matters when OPEC banned oil exports to the U.S. as a way of retaliating against U.S. support for Israel. Oil prices got another boost in 1979 when the Iranian revolution temporarily took Iran's oil production away from the world market. Throughout the 1970s, the U.S. was a net importer of growing amounts of crude oil, needing more than 8.0 million barrels per day (bpd) by January 1980 (Energy Department statistics available at https://www.eia.gov/…).

Today, the U.S. is a small net exporter of crude oil, but domestic crude oil production has been limited by financial losses suffered during the initial pandemic in 2020. According to Thursday's report from the U.S. Energy Department (DOE), crude oil production totaled 11.9 million bpd last week, still short of the pre-pandemic peak of 13.0 million bpd.

By the time Paul Volcker took office as the chairman of the Federal Reserve in August 1979, price pressures were already at a fever pitch, climbing up 11.8% from a year earlier with the federal funds rate at 11.3%. Once in office, Volcker and the Fed allowed the federal funds rate to reach the breathtaking peak of 19.8% in March 1980, followed by a second, even higher peak of 22.0% in December 1980.

P[L1] D[0x0] M[300x250] OOP[F] ADUNIT[] T[]

Our fallible memories have a tendency to put a bow on it and say we all lived happily ever after, but there was more to the story, and it involved oil policy. Spot crude oil prices hit a peak of $39.50 a barrel in the summer of 1980, over 11 times the price it started at in 1970.

When President Nixon took the dollar off the gold standard, he also put price controls on domestic oil, and it had the unwanted effect of discouraging production. President Jimmy Carter set a plan in motion to phase in deregulated fuel prices in 1979, but prices stayed high until after President Ronald Reagan took office in January 1981 and removed the remaining price controls that were limiting production.

With increased supply from growth in non-OPEC production, U.S. reliance on oil imports fell from over 8.0 million bpd at the start of 1980 to less than 4.0 million bpd by the spring of 1982, allowing spot oil prices to fall below $30 a barrel and on to lower levels later.

I mention this piece of the puzzle because in this age of going green, there is a reluctance to encourage long-term production of oil and gas, production that is needed to break the West's dangerous dependence on Russia and OPEC for its energy needs.

There seems to be a notion in the popular press, reinforced by the Federal Reserve's statement on Sept. 21, that, somehow, higher interest rates are the primary solution to today's problems. It reminds me of the father in the comedy, "My Big Fat Greek Wedding" who believes Windex can cure anything.

As I have often stated, the Fed can raise interest rates and can help slow the economy, but it cannot produce fuel, make crops grow in a drought or make Russian President Vladimir Putin go home and put his weapons away. The more important solutions to today's problems are beyond the Fed's reach.

Intending to enact Volker's cure from the 1970s, the Fed has missed two important points. First, there is no lack of confidence in the U.S. dollar as there was in the 1970s. Today's U.S. inflation is not a currency problem.

Second, by putting the burden of the outcome on the height of the interest rate, the Fed is vulnerable to creating a painful economic environment of both high prices and high interest rates. Without a coordinated effort to increase production of the essential goods that are in short supply, the high interest rates can increase economic pain, but little else.

In the U.S. ag sector, we currently have extremely tight supplies of corn, soybeans, wheat and other crops traded by speculators that are frequently worried by the hawkish path the Fed is on. Facing tight supplies, high prices of fuel and fertilizer, perennial competition from Brazil and the uncertainty of weather, the profitability of the next season is never certain.

As we add to the list of risks the potential for further hostile acts from Russia, Iran and OPEC, we can quickly see that Fed policy is one important tool in this nest of problems, but it should not consider itself the primary tool. It took a lot more to end the inflation of the 1970s than just raising interest rates, and we will need a more comprehensive approach today. Interest rates are no Windex.

**

Comments above are for educational purposes only and are not meant as specific trade recommendations. The buying and selling of grain or grain futures or options involve substantial risk and are not suitable for everyone.

Todd Hultman can be found at Todd.Hultman@dtn.com

Follow him on Twitter @ToddHultman1

(c) Copyright 2022 DTN, LLC. All rights reserved.