Beef Producers Gain Ground in Battle for Mandatory Country of Origin Labels

Label Wars

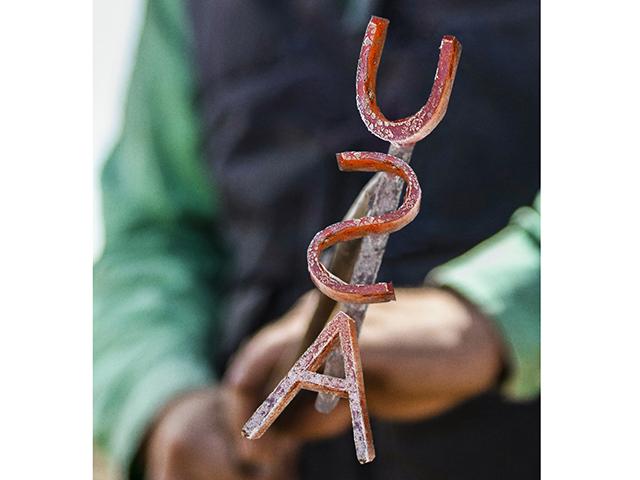

Like a hot branding iron, the repeal of Mandatory Country of Origin Labeling (MCOOL) left a mark on America's beef business. Seven years later, it's a scar that continues to fester.

"Congress has heard from the countryside on this," says Lia Biondo, director of policy outreach for the U.S. Cattlemen's Association (USCA). "If they haven't heard us, they aren't listening."

It was 2015 when the World Trade Organization (WTO) agreed with Canada and Mexico that MCOOL gave U.S. beef and pork a marketing edge. Those countries threatened an estimated $3 billion in annual retaliatory sanctions against U.S. beef and pork exports if MCOOL wasn't withdrawn. It was enough for legislators to back down, fearing the price was too steep for any gain that might be realized.

Texas Congressman K. Michael Conaway, who retired in 2021, was then chairman of the House Agriculture Committee. He said at the time: "The starting point needs to be that Mandatory COOL for meat is a failed experiment which should be repealed." And, in fairly short order, it was. Since then, America's cattlemen have continued to press the issue.

REINSTATING MCOOL

The American Beef Labeling Act is one of the most talked-about legislative attempts to reinstate MCOOL. It's something the USCA's Biondo says her group fully supports. But, she believes it will take increased pressure from voters to push the bill through.

"We've been shouting from the rooftops that this bill [the American Beef Labeling Act] is something we need to move forward. But, being candid, I'm not sure it will move forward. We are calling on producers to reach out to members of Congress and to press them on the issue. Unless legislators hear from the countryside continuously and loudly, I don't know if we can move that bill, because there's a lot of opposing pressure."

In the U.S., much of this pressure has come from organizations representing meat packers and processors, including the North American Meat Institute (NAMI). Sarah Little, vice president of communications for NAMI, in response to questions about the group's current position on MCOOL, wrote: "The Meat Institute opposed Mandatory Country of Origin Labeling and will participate in the rulemaking process when USDA proposes new regulations."

Despite the pushback, last year, Sen. John Thune (R-SD), introduced the American Beef Labeling Act, saying producers in his home state had worked tirelessly through the pandemic to continue to produce some of the world's highest-quality beef, and they should be recognized for it.

"The pandemic only highlighted their important role in our domestic food supply and the urgent need to strengthen it," he says. "To ensure the viability of cattle ranching in this country, the system in which producers operate must be fair and transparent."

At press time, an identical House version of this bill was introduced by Rep. Ro Khanna (D-CA). It also had bipartisan support.

While the possibility of tariffs still represents a significant barrier to MCOOL, Biondo notes the American Beef Labeling Act specifically states any labeling program would have to be WTO compliant.

Along with concerns about tariffs, Biondo says they've heard from processors who insist there will be significant costs tied to sorting out U.S. beef in their facilities if the American Beef Labeling Act moves forward. "I ask them to look at their record profits," Biondo says in response. "They can certainly afford to give back to the producers in this country."

DEFINING U.S. BEEF

Another legislative attempt to alter today's labeling landscape is the U.S.A. Beef Act. The Senate version was introduced by Sen. Mike Rounds (R-SD); the House version was sponsored by Rep. Matthew M. Rosendale Sr. (R-MT). The two bills are identical and have bipartisan support.

In this case, the phrase "Product of U.S.A." or any substantially similar word(s) could only be used if beef was exclusively derived from one or more cattle born, raised and slaughtered in the United States. It would not apply to product intended and offered for export. This is not Mandatory Country of Origin Labeling but a way to limit the use of words or phrases that imply a product originated in the U.S. when it did not.

On introducing the bill, Rounds said, "We must fix the current labels to protect consumers and producers. For far too long, South Dakota producers have suffered as their high-quality, American-raised beef has lost value as it's mixed with foreign beef raised and processed under different standards. This is wrong. Consumers deserve to know where their beef comes from, and accurate transparent labeling supports American farmers and ranchers. It's long past time we fix this once and for all."

MCOOL HAS A CHANCE

For R-CALF USA, the fight to bring back MCOOL has been long and all-consuming.

Bill Bullard, CEO for the group, believes the beef industry is on the brink of a major shift in labeling thanks to the American Beef Labeling Act. "I feel confident we will get MCOOL reinstated, and I'm hopeful this will happen by the end of the year. I can finally say it's now a matter of when and not if," he adds.

R-CALF is throwing all of its support behind the American Beef Labeling Act. Bullard says this is their preferred approach because it requires all beef sold at retail be labeled as to its country of origin. He believes the U.S.A. Beef Act would only limit the ability to continue to "misuse the label."

P[L1] D[0x0] M[300x250] OOP[F] ADUNIT[] T[]

"Packers have been allowed to use voluntary labels for decades, but they don't because it's not in their economic interest," Bullard explains. "We don't believe a voluntary program can be successful."

He says packers today sell beef from up to 20 countries with stickers that indicate it is USDA inspected, and it may be quality graded and labeled a Product of the USA. Bullard insists it is not in the meat packers' economic interest to disclose to consumers where their beef is sourced from.

"The packers have tremendous political clout and undue influence, and that's why it's been so difficult to reinstate Mandatory Country of Origin Labeling for beef," he adds.

THE REGULATORY ROAD

While Bullard is optimistic about the legislative path for reinstating MCOOL, others believe the challenge in doing so is nearly insurmountable. As a result, a regulatory fix continues to gain traction on Capitol Hill.

The USCA's Biondo is hopeful the USDA's regulatory process can solve the labeling problem by better defining what "Product of the U.S.A." means in regard to beef. Today, under USDA rules, beef is considered to be a product of the United States if it's processed in this country. The agency announced last year following a Federal Trade Commission vote that it would review the label as it applies to meat managed through the Food Safety and Inspection Service.

Biondo believes if there is a regulatory way to close the loophole that allows foreign beef to be labeled as Product of the U.S.A., the industry will be light-years ahead of where it is today.

Danielle Beck agrees and says this is where the National Cattlemen's Beef Association (NCBA) has been focusing much of its work.

Beck is senior executive director of government affairs for the group. She believes proposals on the table that would reinstate MCOOL have a low likelihood of moving forward, but there are real opportunities to reform labeling on the regulatory front.

"At NCBA, we think it is a better approach to reform labels that are voluntary, auditable and trade compliant. The current label has the potential to be misleading, it's generically approved and can therefore be used liberally by retailers and packers. We don't believe there is any benefit to the producer with regards to the labeling that is in place today."

R-CALF's Bullard, however, remains resolutely against any labeling program that is voluntary.

"The rulemaking process to ensure that only beef raised here is eligible for the 'Product of the U.S.A.' label would not require any labeling of foreign beef," he says. "We believe that once the American Beef Labeling Act passes, it will negate the need for these voluntary labels. But, we recognize these are independent processes. The USDA is working to establish its own regulation, and Congress is looking to intervene legislatively."

THE PREMIUM QUESTION

NCBA's Beck says the USDA has reviewed several petitions on this issue, including one submitted by NCBA requesting the agency eliminate the "Product of the U.S.A." label altogether, replacing it with more appropriately descriptive terms like "Processed in the U.S." She believes the real value for cattle producers lies in creation of more verified sourcing labels, and the NCBA hopes its approach will help accomplish that.

"We think this is the best way to get actual premiums to cattle producers for what they produce," she explains, adding she's concerned that if MCOOL is reinstated, there will be a substantial cost because of noncompliance with WTO rules, which would outweigh any benefits.

"Why do that? It is a questionable approach in our minds, especially when the intention now with the USDA is to reform the label in a manner that is trade compliant," Beck says.

She believes there is a greater possibility for premiums at the producer level tied to verified sourcing. According to IMI Global, a company that provides voluntary, third-party verification programs to producers worldwide, there are dollars tied to label claims. The 2018-2020 average per-head premium in beef, based on different labeling claims, ranged from $9 per head to $56 per head.

Beck adds that as regulatory changes take place, the future for the cattle industry is bright.

"During the height of the pandemic, we saw consumers' perceptions and attitudes change, and demand for beef continued to grow. We want consumers to be able to pick and choose based on what makes sense in terms of their own individual preferences and budgets," she continues. "We don't want government-mandated programs that force a label on everyone across the industry. It's a disservice to consumers given food prices now, and a government-mandated program won't deliver meaningful benefits back to our cattle producers either.

"Rather than relitigating an issue that won't benefit us financially, we have to pivot and find a way to empower producers and consumers," Beck says. "Let U.S. cattle producers decide how to best market their own products. And, then, let the consumer, armed with that information, make their own buying decisions. Cattle producers are always their own best advocates, and they should reap the benefits from any specialized labeling claims."

MCOOL'S VALUE QUESTIONED

Emotions drive a lot of discussion when it comes to MCOOL, but as an agricultural economist at Kansas State University, Glynn Tonsor follows the data. He says the numbers haven't really backed up the idea that MCOOL improves demand for U.S. beef.

In 2015, prior to the repeal of MCOOL, Tonsor delivered a 196-page report to Congress on the likely effect of repealing MCOOL. He showed that when MCOOL was active, there was not higher demand for beef. Tonsor updated his overview of MCOOL in 2019 and came to the same conclusion. Three years later, the question is whether COVID has changed consumers' views.

"Make no mistake, meat demand, domestically and abroad, is definitely stronger than it was in 2019," Tonsor says. "Higher demand is not the same as saying consumers have more of an interest in origin labeling. I remain skeptical that people would pay more today based on MCOOL policy than they would pre-COVID."

He says that in aggregate for the beef industry, he believes reinstating MCOOL will lead to a net loss.

"That's what I showed in the 2015 report, and I think the core mechanics are similar today," Tonsor explains.

"It's important to note that of the beef consumed in the U.S., about 15% originates outside of this country. So, about 85% of the beef consumed here was produced here. If we move to mandatory labeling, that would have a cost on 100% of the beef sold. It would all have to be sorted and labeled differently, and there is a cost as that animal is slaughtered and tracked, and sorted throughout the entire system. So, the cost is on 100% of the beef, but for 85% of the beef, it is just clarifying origin. That means there is a high burden on the minority of volume to offset systemwide costs, and there is no evidence of a demand boost as a result of it."

LABELS AND PALATABILITY

Marketing labels do have a lot of power, though, even the power to affect palatability. Keayla Harr, a KSU student, did her master's thesis on that premise, and her work had surprising results.

Consumers taking part in Harr's research were provided false labeling information on ground beef patties. They believed beef labeled as grass-fed was much better in terms of tenderness, juiciness, flavor and texture. In reality, all of the ground beef (80% lean and 20% fat) they ate came from the same production lot/day, and it was bought in chubs. Each chub was divided into patties and went randomly to a consumer panel. Those patties were randomly assigned label terms, including those indicating the beef was all natural, raised without antibiotics, raised without added hormones, fresh never frozen, grass-fed and organic. Consumers were asked to evaluate the patties.

The research team, headed by Harr, included Erin Beyer and Kaylee Farmer, and was led by professor Travis O'Quinn as principal investigator. The group reported that adding production claims consumers recognized made for a better eating experience. They added that events of 2020 and 2021 had set the stage for consumers to be more adapted to wanting foods they believed to be locally sourced, which influenced the results. The researchers noted there is a perceived "quality halo" around locally produced products even when, as in this case, there was actually no real difference.

While palatability and demand are two different things, the potential for one to influence the other is clear.

Karr, whose family raises beef in Ohio, says looking at how different labeling could shape the perception of taste and flavor was interesting, and not really something she expected.

"For me, it all goes back to the cues we are giving buyers. Our labels tell the story of our beef, and they create a difference in consumers' minds. I think the telling thing here is that we need to give buyers more choices, and by doing that, we can also increase demand for our product."

KEEPING TRACK

MCOOL: Mandatory Country of Origin Labeling was born out of the 2002 farm bill, but it was repealed for beef and pork in 2015. Today, Country of Origin Labeling is still the rule for commodities including lamb, chicken, goat, wild/farm-raised fish and shellfish, perishable agricultural commodities, peanuts, pecans, ginseng and macadamia nuts.

U.S.A. Beef Act: This bill was introduced in both the House of Representatives and the Senate in August 2021 with bipartisan support. It prohibits the labeling of cattle meat, or a meat food product of cattle, from bearing the phrase "Product of U.S.A." unless such product was exclusively derived from one or more cattle born, raised and slaughtered in the United States. It would not apply to product intended and offered for export.

American Beef Labeling Act: As a Senate bill, this was first introduced by Sen. John Thune (R-SD) in September 2021. An identical House version of the bill was introduced in March 2022 by Rep. Ro Khanna (D-CA). Both bills have bipartisan support. If passed, it would require the United States Trade Representative, in consultation with the Secretary of Agriculture, to "determine a means of reinstating Mandatory Country of Origin Labeling for beef" in a way that will be in compliance with all applicable rules of the World Trade Organization.

FAKE MEATS FIGHT THEIR OWN LABELING BATTLES

There's another front on the label wars, this one between beef producers and manufacturers of "fake meat." The use of the word "meat" or even "beef" on protein-based product continues to be an issue for the beef industry. Danielle Beck, senior executive director of government affairs for the National Cattlemen's Beef Association (NCBA), says this is a high-priority area as they work to avoid winding up where the dairy industry is today.

"Mainstream and liberal media often portray these products as disruptive and as coming for beef's market share," Beck says. "They are still less than 1% of the market. Over a decade, there's been very little growth in their market share."

That doesn't mean they aren't a threat. Beck notes that investors in this technology include packers. "We all need to remember that meat packers are protein companies, they are not beef companies," she says.

Tyson Foods, for example, continues to back plant-based and lab-based technologies investing in Beyond Meat, Memphis Meats (rebranded in 2021 as Upside Foods) and Future Meat Technologies. In 2019, the group released its own brand, Raised & Rooted, that blends meat and plant ingredients. JBS launched a plant-based burger and announced a protein brand launch. Despite the interest and innovation, companies like Impossible and Beyond cut prices and saw sales decline during COVID. Nevertheless, consulting firm Kearney reports projections look for these global markets to reach $450 billion by 2040.

[PF_0522]

(c) Copyright 2022 DTN, LLC. All rights reserved.