Vise Tightens on Wheat Stocks

World Wheat Supplies Tighter, but Warning Signs

USDA rolled out their first official World Agricultural Supply and Demand Estimates (WASDE) supply and demand forecasts for the 2022-23 marketing year. That statistical year begins June 1 for wheat and Sept. 1 for corn and soybeans. They do their best to shoehorn production cycles in two opposite hemispheres and 12 months into one comprehensive picture. This is the first shot at the new crop and there will undoubtedly be revisions. While many are focused on corn and soybeans, I'd like to draw attention to the crop with the biggest price moves following the report -- wheat.

In a previous DTN column, I likened the wheat stocks situation to putting something in a vise. You need to tighten it a little just to hold it in place, i.e., keep prices from going down. Further tightening can distort the item, and even further tightening can sometimes result in breaking what you were trying to fix. Too much tightening in marketing terms results in a short crop/long tail price formation. You get a big spike in prices, but kill off demand and attract production, resulting in an extended period of lower prices to restore market equilibrium.

That vise is still tightening.

P[L1] D[0x0] M[300x250] OOP[F] ADUNIT[] T[]

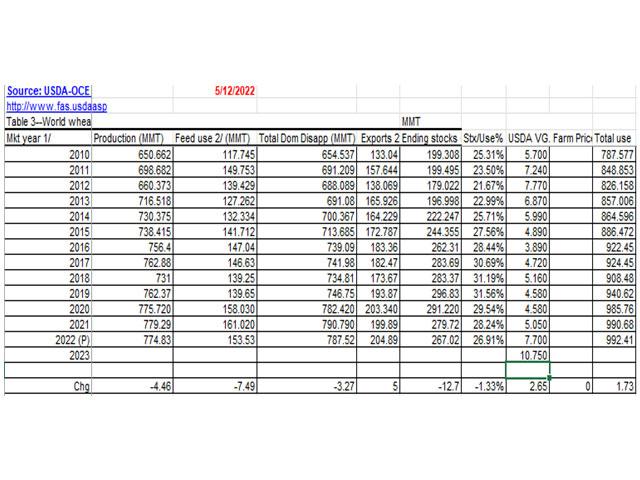

USDA's projected world ending stocks of 267 million metric tons (mmt) would be the tightest since 2016. On a stocks-to-use ratio, the 26.91% would be the tightest since 2014's 25.71%. The USDA "VG" column is average cash price and lags a year. We assume 2022-23 production is tied to the price signals from late 2021, so pair that data with last year's average price. You can still see that as the world stocks-to-use ratio has tightened, U.S. average cash prices have risen. On Thursday, May 12, USDA projected a record high for U.S. cash average price in 2022-23, at $10.75 per bushel. This is across all wheat classes and, typically, soft red winter (SRW) wheat would be lower and high protein spring wheat would be higher than the overall average. Yes, there are exceptions due to individual year shortages.

I do feel the need to dissect the data a little further. The Russian invasion of Ukraine is getting a lot of "credit" for the surge in wheat prices, but there are some countervailing trends. The market responds to price signals and short crops tend to have long tails (extended price declines once the shortage is resolved by attracting production and discouraging consumption).

USDA was much more comfortable marking down the 2022 Ukraine crops Thursday, as the war continues and infrastructure is damaged. Wheat production two years ago was 25.42 mmt, surging to 33.01 mmt in the current marketing year. USDA is now looking for 21.50 mmt to be harvested in 2022. That's a big drop from last year, but last year was unusually large. Ending stocks are seen growing to 6.01 mmt versus only 1.5 mmt two years ago, due to shipping difficulties.

It has been popular to assume reduced exports out of Ukraine due to the war and out of Russia due to trade and banking sanctions. USDA isn't buying into the latter idea. Russian exports dropped to 33 mmt in 2021-22, but the Outlook Board currently sees them reverting to 39 mmt in 2022-23, about where they were two years ago. The Dictators Are Us Club will buy, despite the sanctions, and other countries will find a way to get around them if the price discount is significant enough.

The other thing to consider is market response to $10 wheat futures and the vagaries of weather. Aussie production is expected to drop off from last year's record 36.3 mmt, but Canada is expected to rebound to 33 mmt from the drought impaired 21.65 mmt in 2021-22. USDA nicked Indian production due to high (try 115 degrees) temps, but sees their exports at 8.5 mmt versus 8.15 mmt in the current marketing year and only 2.56 mmt two years ago. Those supplies are not typically available to the world market at lower price levels, but "come out of the woodwork" at $10.

Bottom line? Tightening world stocks-to-use ratios should keep a bid under wheat and keep the average price for the year comfortably above last year's $7.70. That assumes producers take advantage of the forward contracting opportunities that are available. There are warning signs of supply leveling out, however, as various countries around the world respond to the historically high prices. Some of that is on the production side. Don't overlook demand destruction either. This initial WASDE estimate has world wheat feeding use dropping to 153.53 mmt versus 161.02 mmt in the year wrapping up.

Alan Brugler may be reached at alanb@bruglermktg.com

(c) Copyright 2022 DTN, LLC. All rights reserved.